NEMI 2025 Notes

tl;dr: I shared some work on counterfactual analysis of CoTs at a Mech Interp workshop, supported by a Cosmos+FIRE grant. See the technical details.

This year I had the pleasure of engaging in some mechanistic interpretability research. I was specifically curious about the causal structure of chain-of-thought reasoning used by models like OpenAI's o1 or DeepSeek's R1 to solve mathematical problems. What I learned is that these models' chains of thought are deceptively interpretable; that is, at first glance they appear to be thinking in human terms, but counterfactual analysis reveals the real mechanisms of "thought" to be far stranger, with a strong dependence on punctuation and certain expressions that mean to the model something other than what they would mean to a human.

The traditional autoregressive transformer architecture for a language model generates a single token in each forward pass. There is a certain amount of computation that can already happen in that single forward pass: models can add even several digit numbers together without any reasoning tokens or tool calls. However, more complex mathematical problems apparently exceed the computational power available in that single forward pass of the model. Reasoning models extend the compute available by generating a block of thinking tokens before giving the final answer. Through a training regimen pioneered by OpenAI in o1 and published openly by the DeepSeek team with their R1 paper, these models can be trained to do something that looks like reasoning, and it does well on mathematical benchmarks when the problems are similar to problems it has seen in training. As the training data is expanded, presumably with mid-training curricula interleaving mathematical and coding problems, these models are gaining significant utility in automating certain tasks in software engineering and assisted proof solving.

There are however serious shortcomings, one of which is that the models still make mistakes even on problems that we would expect to be well within the capabilities. We see this most starkly when working with a base model that has not been explicitly trained for reasoning, as you can read in my post on errors in DeepSeek V3 Base. (Incidentally, DeepSeek V3 Base may be the last model on which we can run this experiment: models trained after mid-2025 will likely contain examples of reasoning traces in their training data.) Reasoning models seem to make much of the same errors just at a somewhat lower rate, and buried deeper in their longer reasoning traces.

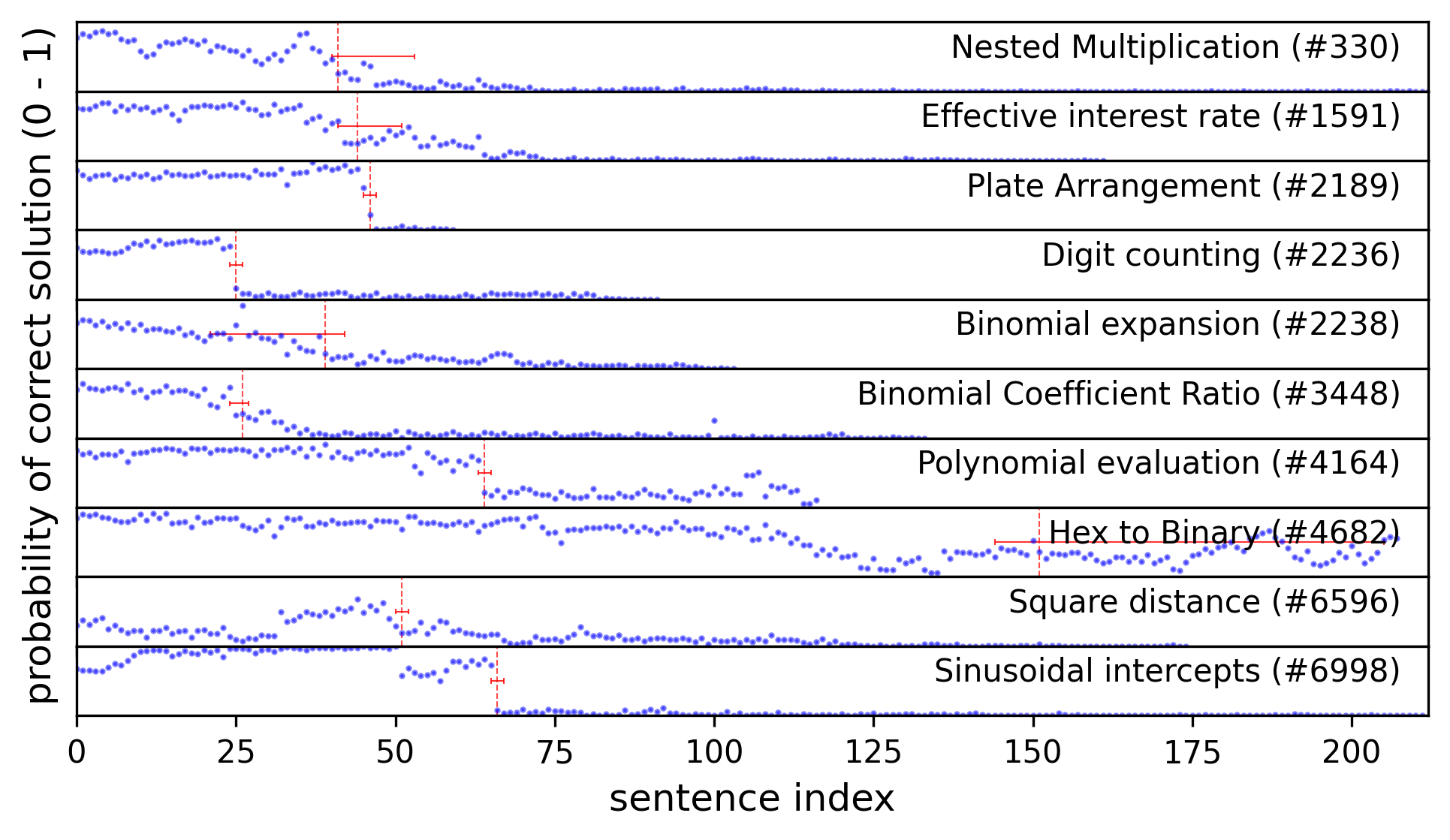

As I was working through some V3 Base traces manually, it occurred to me that it should be possible to find the exact location of the first error in a faulty chain of thought using counterfactual methods similar to what I had worked on some years earlier. I applied Bayesian changepoint detection and active sampling to quickly find the errors in traces of the recent Bogdan & Macar paper, and presented a poster on the topic at NEMI 2025.

At the NEMI poster session I met Eric Bigelow, whose work at Harvard took him down very similar paths, or I should say nearby Forking Paths.

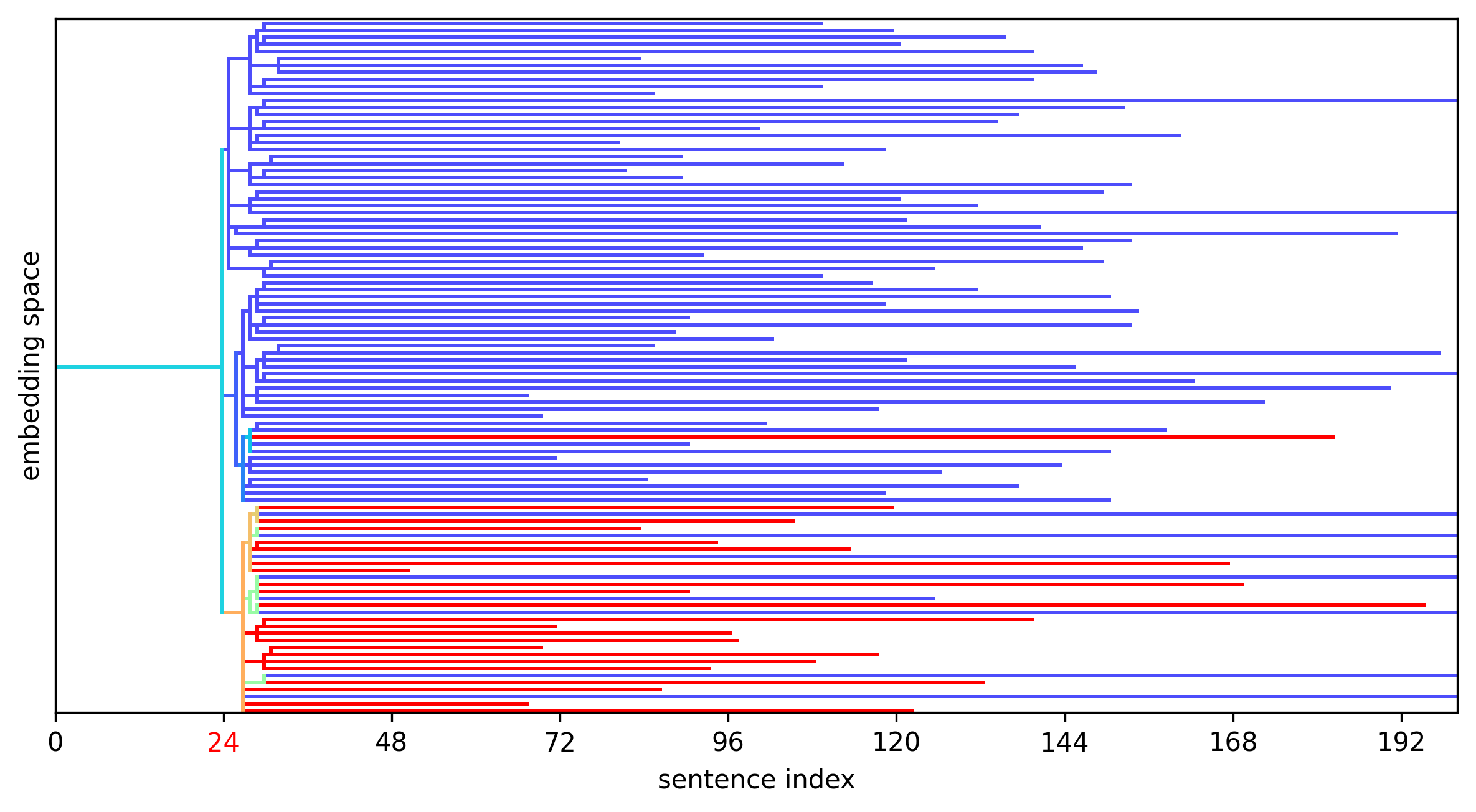

One of Eric's team's findings was that a lot of counterfactual weight was on punctuation marks.

These "forking tokens" such as an opening parenthesis ( were likely to be places where

the probability of successful answer changed precipitously. My work went down only to the

sentence level rather than token level, so I cannot directly compare, but other work

such as this paper by Chauhan et al. provides some

more mechanistic explanation for how these punctuation marks function inside relatively small open-weight models.

I also had the opportunity to have an extended discussion with some folks on the research team at Goodfire who are doing interpretability as a service. Their focus seemed to be mostly on visual and bioinformatics models rather than reasoning, likely because the target market for MIaaS is more around domain-specific models that work in non-text modalities. Nonetheless I was able to rubber duck some things.

I was left with the impression that the line of inquiry I was following is impractical. The causal structure of chains of thought is just as messy as the weights inside the models. Although it appears easy to read, the actual workings are highly complex, inefficient, and alien. These so-called "reasoning" models are the latest search technology, and have their utility, but should always be paired with formal verification, and in cases where this is not possible, there is a great risk of biasing human readers with convincing-sounding model outputs.

I do believe that mech interp techniques can and should be applied to studying structure in CoTs, but this is not going to be easy, it just looks that way because the "thoughts" appear to be in English. (I am morbidly curious what the CoT would look like after applying strong optimization pressure to shorten the CoT while maintaining performance. Would RL/GRPO be sufficient to develop a shorthand language?)