Questions of Chinese Grammar

For some time I have fretted over which Asian language to learn. Japanese appeals to me for its sweet sound, and because I take interest in Japanese artwork (particularly the video games and animated films) that they have produced. However, I have rarely met Japanese-speaking people. Chinese is much more utilitarian. Just the sheer number of Chinese speakers and China's recent economic success ensures that any student of Chinese will have ample opportunity to practice. For this reason, I have chosen to study Chinese.

Once deciding on Chinese, you have to pick a dialect and character set. The Mandarin dialect is the natural choice because of its popularity. Choosing a character set is a bit more difficult. I again followed the popularity and chose the simplified character set to learn first. I'm also taking a look at the traditional versions of characters every once in a while, mainly so that I can identify text written in traditional characters.

Now I want to share some of the things which have amazed and puzzled me about Chinese so far, particularly certain aspects of grammar.

Many Dialects, One Written Form¶

First, the facts:

- There are several mutually unintelligible dialects of spoken Chinese, the most popular being Mandarin, Wu, and Cantonese.

- In each dialect, each character is associated with (typically) a single syllable.

- Speakers of different dialects read the same books and can write letters to one another and be understood.

This seems to indicate that the grammars of the several dialects are identical. I wonder how similar the grammars of the spoken dialects are in practice. I suspect that there are significant differences in spoken grammar between dialects and that when a Chinese speaker writes, he uses a formal written grammar which is taught throughout the Chinese-speaking community. This hypothesis could be tested by comparing literal transcriptions of conversations taking place in different dialects. Perhaps in novels this would be noticeable.

Five Ways to Say "Brother"¶

When I was in Beijing, I was asked frequently about my family. I got the impression that family plays a more central role in Chinese culture than it does in the West. This shows in the language as well. The four Chinese words meaning "brother" that I have learned are:

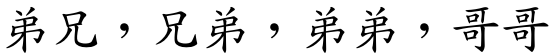

dìxiōng, xiōngdì, dìdi, gēge

So far as I can tell, the closest translation for the English "brother" is "dìxiōng". The closest translation for "brothers" is "xiōngdì". However, whenever possible, a Chinese speaker will specify the relative age of the brother being referred to by using "dìdi" (younger brother) or "gēge" (older brother).

If we look at the character level, we have three characters. "Dì" means younger brother, which is apparent from the word "dìdi". Similarly, "gē" means "older brother". To complicate matters, we also have "xiōng" which my dictionary (CDICT) defines as meaning "older brother". This definition makes sense in light of the nearly symmetric words for "sister". But if I start talking about sisters, I might be tempted to talk about some of the other incredibly specific terms for sisters-in-law, uncles, grandfather's nephews, and so on. Just one example from the other relations I want to point out. There are single characters which distinguish between paternal uncles:

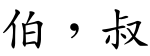

bó, shū

"Bó" means "father's older brother" and "shū" means "father's younger brother". Amazing.

Concept of Physical Space¶

Although I have been studying Chinese for some time now (on and off this summer, and then more intensely in the past three weeks), I have managed to avoid reading too much about Chinese. I'm enjoying this approach, as it gives me the chance to work out the grammar rules and the Chinese ways of thinking for myself. So far the most interesting grammatical difference between Chinese and the Western languages is the Chinese concept of physical space. Now, I'm really guessing here. The suggestions I'm about to make are from learning without referencing grammatical explanations in English, and so they may be completely off-track. I look forward to reading a good book like Essential Chinese Grammar, and returning to these early ideas to see how my understanding develops.

Ok, enough delay. I want to point out some example sentences, and try to draw some conclusions about Chinese grammar.

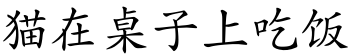

māo zài zhuōzi shàng chīfàn = The cat is on the table eating.

As a first example consider the sentence "māo zài zhuōzi shàng chīfàn" meaning "The cat is on the table eating" (or, translated word-for-word: "cat-at-table-on-eat"). When you first approach this sentence, the relationship between the several words is not clear (at least not to me). To help clarify, we take another related sentence:

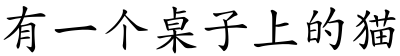

yǒu yìge zhuōzi shàng de māo = There is a cat on the table.

First a note about the correctness of this sentence: I generated it through Google Translate. A first sign that this sentence is not quite grammatically correct is that the classifier "ge" is used where "zhī" should have been used (we say "zhī māo" not "ge māo"). But, if we let that slide, there is a very interesting feature of the sentence I want to look at. We see that the phrase "zhuōzi shàng de" acts as a modifier on "māo". If this is good Chinese, and not just Googlecruft, it means that physical spaces (such as the region which is above the table, represented by "zhuōzi shàng") may be used as modifiers on objects which exist within that space. The closest translation in English for "zhuōzi shàng de māo" would be "the cat which is on the table". In German we can get a little closer by using an extended adjective construction to place the spatial modifier before the noun: "die auf dem Tisch seiende Katze".

This concept of physical spaces represented by noun+preposition can be seen in the more verbose way to say "There is ...":

zhè lǐ yǒu yìzhī māo = There is a cat.

Here we have "zhè lǐ yǒu ...", literally "this-in-have ...". I suspect that we can parse this as "The space which is inside this possesses ...". Such an interpretation would suggest that the following constructions are possible:

zhuōzi shàng de māo zài chīfàn ?=? The cat on the table is eating.

zhuōzi shàng yǒu yìzhī māo = There is a cat on the table.

Or maybe it is totally incomprehensible. I'm excited to advance enough in Chinese to get more insight into this concept of physical space and how it may be applied in the language.

Originally published on Quasiphysics.